The Start of the Twentieth Century

By 1900 education for everyone was, in theory at least, free up to the age of 11, and most schools were coming under the increasing influence of School Boards or Local Education Authorities. This must have affected staying-on rates, attendance rates and what was being taught. In 1904 the boys’ school, which was intended for 60 pupils and was under the headship of Mr Vernon Swift, had an average attendance of 56, but the girls’ school, which had been built for 80 and was under the guidance of Mrs Julia Hellier, had an average attendance of 96. There must have been many days when there were about 160 children on this cramped and problematic site. In 1911 there was a major reorganisation in Walsham, which saw the amalgamation of the boys’ and the girls’ schools to create a mixed school. This coincided with a building programme which included the creation of a new classroom next to the road, (now the workshop), and the extension of the former boys school on the far side of the river. The roadside building is made of high quality “white” brick, probably to match the now demolished room next to it, but the other extension is of rather cheaper red brick.

One of the inherent weaknesses of the school site was exposed dramatically in 1912 when it and much of the surrounding area flooded. The floodwater rose rapidly and Miss Kirby had to be rescued from the upstairs window of the School House along with the mistress from the infant school. The water in Miss Kirby’s classroom was about five feet deep and part of the back wall near to the river fell down. There was considerable damage and destruction in this part of the village and a relief fund was set up which raised £22.2s.8d; the Relief Committee distributed the money according to loss and the surplus was put towards repairs to the school. The area was to flood again in 1938 and 1968.

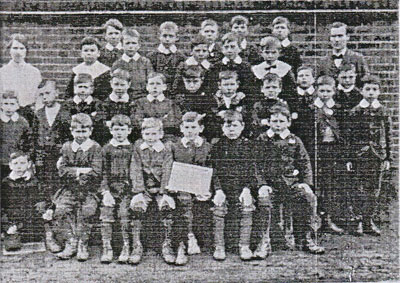

There had been constant changes in teaching staff between 1885 and 1915, but May1st 1916 saw the arrival of Mr Vincent J.E. Dove. He came into a mixed school, which now had 182 pupils, and he remained as headteacher for over thirty years, spending much of his time teaching in the classroom nearest to Bridge House. Mr Dove is one of several headteachers whose careers in Walsham can be traced thriugh the school Punishment Book. The book opens in 1907 with Mr Smith in charge. The first entry is for George Sullivan who was eight and had been discovered “stealing his foster mother’s milk money and spending it on sweets” – he received a “severe caning of the buttocks”. Mr Smith does appear to be from the “spare the Rod and Spoil the Child” school of thought, although in mitigation, he was dealing with those extremely crowded conditions before the school was extended. He used the cane several times each month for such things as “throwing a boy’s cap into the ditch”, “very careless work in arithmetic”, and “teasing an old man”. Every once in a while Mr Smith does seem to reach his limits: in May 1908 there is stone throwing in the playground with stones thrown into the stream, at the school fence, and one stone cracks a window in the girls school – 14 boys are lined up and caned. There is also the case of the boy “insulting a girl saying very rude words” for which he receives “a severe thrashing of buttocks and shoulders”.

When the school is enlarged and reorganised into a mixed school Mr Hine is the headteacher. You feel that he may well have been trying to establish a new, disciplined environment and starts by caning 14 different children in his first 7 weeks. Later in the year on 14th July he canes Joseph Newstead for truanting – he had rather imaginatively gone home and told his mother that the summer holiday had already started! Mr Hine was, like his predecessor, a very regular user of the cane, and interestingly he clearly felt that his responsibility and authority went beyond the school gate. Young Newstead was also caned for “annoying an old lady riding a tricycle in the street last evening”, and another boy was severely thrashed for “writing obscene language on the door of the fire station”.

Mr Dove appears to have represented a change in attitude towards corporal punishment; he canes people on perhaps two occasions each year, there are seldom more that two strokes of the cane, and he often produces long explanations in the Punishment Book as to why he has had to use this form of punishment. His first entry on the 16th July 1915 was for a boy who had been “throwing stones after a monitor on his leaving school” – it now seems strange that the school was still using a monitorial system at this date. Although the second great Education Act of 1918 had raised the school-leaving age to 14 the head seldom resorted to the cane – throughout the 1930s he used it only four times, and not at all during his last four years in post. Infrequent use occurs during the early 1950s and the cane is not used at all after July 1954 until the final entry: 16th October 1962 – Raymond Harris – 8 -“biting another boy”.

After the Second World War

The 1940s probably represent the greatest period of social change in modern British history and the 1944 Education Act, (often called the Butler Act), had enormous repercussions for village schools. The school-leaving age was now raised to 15, the old system of all-age elementary schools was abolished, and a new national system of secondary schools was introduced. It would take 20 years for the full implications of this Act to permeate Walsham, but the late 1940s were quite difficult years during which the school prepared for change. The old boys school had always been overseen by the Diocese, which owned the site south of the river, but the origins of the old girls’ school were far less clear and there was much discussion about the ownership of the land next to the road. In 1947 it was decided that the school should become Voluntary Controlled rather than Aided and the Local Education Authority took over all responsibilities. The School House remained under church control and rent for the teacher’s house continued to go to the Doicese; it was also agreed that when a new school was built the proceedings from the sale of the old site would also go back to the Diocese.

Parent Power

The wave of post-war socialism was paralleled by the emergence of parent power. In March 1948 the Managers received a letter from a parent complaining about bullying in the school, and at what may well have been a rather heated open meeting held the next week, over 20 parents voiced a wide range of grievances. Another special meeting was held two weeks later to distil the grievances into 13 points which were sent to the Chief Education Officer; at this point the Rev. A.C. Briggs, who has been involved with the school for over 30 years, resigns as Chairman of the Managers citing advancing age and increasing deafness as his reasons. The next Managers’ Meeting is held on 10th May and is attended by the CEO and a school Inspector. The HNI had obviously been sent in to check standards and patterns of organisation, and presumably to investigate the 13 points: he reported that standards were generally average and the timetable reasonable – some work was good, children were happy and there was “no jusification for the attacks made upon (the school)” and ” no evidence of unofficial corporal punishment”. The CEO said that the parent-group had no status in the eyes of the LEA and that the involvement of the local press had been regrettable. At the start of this meeting the Managers had received Mr Dove’s resignation.

Miss Olive Kerridge

During this period one of the pillars of education in the village was Miss Kerridge. On 31st January 1921 an agreement was signed to engage Miss Olive Ada Kerridge as Assistant Teacher on an annual salary of £90. As one of the thousands of spinsters produced by the carnage of the trenches she served as a teacher in the village for over 30 years, and must of had an enormous impact on the lives of many local people. When she retired on 30th April 1951 the then headteacher wrote “Miss Kerridge left with the very sincere and heartfelt good wishes and gratitude of the children and staff, who have nothing but admiration for the devotion to duty and love of those within her care, which she never for a moment allowed to diminish: this, though it was known to all that her past two years here have been a struggle against ill health”. On 24th May a farewell meeting was held in The Prioy Room of children, parents, managers and staff – Miss Kerridge was presented with a watch, a handbag, a cheque for £12 and a commemorative book containing comments and artwork produced by the children. Her standing in the community was such that a few weeks later she was appointed as one of the Managers of the school, a post she continued to occupy until the school closed.

The School Site continued to present problems. Space had always been very limited and back at the beginning of the century the girls’ play area had been limited to a narrow strip next to the road, while the boys used a grass area on the other side of the river; this became very muddy after rain and boys often returned to the classroom in a pretty dreadful state. Another long established bone of contention was that the boys had only been able to get to their classroom by going through the girls area – this had regularly been a cause of friction. Now that the LEA was responsible complaints flowed freely from both the headteacher and the Managers. There were problems with paths, the toilets, the footbridge, fences, paintwork, heating and the river undermining the end classroom. By 1955 the headteacher had clearly had enough. On 28th February he writes: “Gravel area in front of school, having lain under snow for some weeks is now beginning to thaw into thick mud”. On March 10th he adds: “Gravel area over which all must pass is now a disgusting morasse into which one sinks 6″-7″ .” The LEA finally surrenders and in November workmen arrive to relay paths and sort out the playgrounds. Unfortunately “one of the workmen….. has a great fondness for children and has been giving them money and sweets. This was not objected to in small amounts but today he has been found to have given a girl as much as 4/6. This the headmaster returned to him. It was kindly explained that, whilst we were sure it was just an expression of his general love of children, it was easy for his motives to be mistaken”.

What everybody in the village really wanted was a new village school, but the countywide demands produced by reorganisattion were enormous. There were secondary schools to be built and many old village schools were in a very inadequate state – Walsham le Willows would have to wait.

The Final Years

On 28th October 1952 notice was given that the new school in Beyton was to open for 1953-54. In September 1953 the 13 and 14-year-olds from Walsham would go to the new school, and in the following September 11 and 12-year-olds would join them. At the same time all remaining education in the village would be amalgamated to create a new Junior and Infant School. (From September 1956 most students leaving the Junior school in Walsham would go to yet another new school in Ixworth).

The Junior and Infant School was officially created at the Easter of 1953 but opened properly in its new format on 15th September. There were three classes: Miss Hayward had 26 infants in Class lll, Miss Sharman had 34 7-9 yrs. in Class ll, and Mr Mitchell had 35 9-12 yrs. in Class 1. Life in the new school had moved on, partly as a result of new technology and new teaching ideas, but also because the school was now part of a group of schools all feeding a higher school. The PTA bought the school its first spirit duplicator at a cost of £29; classes were sometimes walked down to the Priory Room, (which blacked out), to see a filmstrip; on special occasions children were taken into Bury St Edmunds to the cinema. In1953 they saw “A Queen is Crowned”, in 1954 it was “The Conquest of Everest”, and in 1958 it was a film about the Russian Ballet, which may not have had quite the same popular appeal! There were football and netball matches against other schools such as Barningham and in June 1958 there was the first Ixworth and District Primary School Sports. The top class did projects on East Anglia and went on field-trips – one day they toured sites in Suffolk and later they did a contrasting tour of sites in Norfolk.

In the June of 1955 an Inspector arrives to assess the effects of the amalgamation and reorganisation. On visiting a school which had a river running through it, he does appear somewhat bemused by the layout and fabric. There are two teaching rooms next to the road, the practical rooms are on the far side of the river, and Class lll is in a completely separate building some way up the road. However he is very positive about the school and its staff describing it as “a happy and efficient school”; reorganisation has clearly eased pressure on the buildings, and he praises the wide use of the local area for teaching. Like any good HMI he is prepared to chide the LEA reporting that “further amenities, such as water-borne sanitation, will no doubt eventually be provided”.

Getting these buildings to approach anything resembling modern standards was clearly very difficult. Absenteeism was often very high and could reach 50%; in 1953 the Head thought “that the annual epidemics were caused by unhealthy living conditions and lack of piped water and sanitation”. At the time water mains were being laid in the street and he wanted the school to be connected, but when this happened the plumbing consisted of little more than a cold water pipe and a sink. It is amazing to read that on November 24th 1961 “a consignment of Elsan closets has been delivered, 13 in all, to replace buckets and wooden seats now in use in both infants and junior departments”. In February of the next year workmen were laying sewers through the playground.

People began to feel the end was in sight. In 1959 the Managers were asked to think about where in the village a site of 1 3/4 acres might be found which would be suitable for a new school. The choice was very limited and focus soon turned to a meadow at the bottom of Wattisfield Road. In February 1961 the Managers are presented with plans of the new school, but a year later they are told that building work has been postponed because schemes elsewhere have priority; the arrival of the Elsans has obviously pushed Walsham down the list. Eventually building does take place and 1965 becomes the year of the big move. During the Whitsun half-term holiday pupils go into school to help staff with packing; on June 23rd new furniture is delivered, and on the 25th lines of children are helping the Head-teacher to move boxes and books along the road to the new site.

On 28th June 1965 children gathered on the old school site for the very last time. “the children assembled at the old school and after a short talk by the Headmaster concerning arrangements there and conduct on arrival, we made our way to the New School in Watisfield Road, where, despite the intense excitement a little work was done!” The new school held its Official Opening Day on 14th December 1965.

Richard Belson

References

- Bury Record Office:- County Directories, Census Returns, School Log Book

- Managers Minute Book, Punishment Book

- Walsham History Group notes and cuttings

- Dr. Lois Louden re; History of National Society

What the Papers Said

Bury Free Press

January 1910

‘Mr H.F. Hine formerly headmaster of Walsham School Boys School returned to the United States last summer and is stopping at Yale University to complete his B.D. degree. He was ordained to the ministry of the Episcopal Church and has been appointed Dean of Trinity Cathedral in Omaha and chaplain of the hospital in that city.’

February 1920

‘Mr V. Swift who has for some time ably occupied the position of Headmaster at Walsham Boy’s School, has been appointed to a position in the Council Boy’s School in Newmarket.

Since Mr Swift has been in the village he has made many friends who will regret his leaving.

He is a thorough sportsman and has been secretary of the Walsham Cricket Club. He was also choirmaster and organist at the Church. He thanked his friends at a farewell party in the Vicarage when he was presented with a pocket book and a purse containing 11 guineas.’