The Walsham Institute Penny Savings Bank

An unusual Christmas present from my wife, comprising two deposit books, four half year reports and statements of account, notices of meetings, and hand-written notes of correspondence between the Secretary and the Managers of the Bank between 1859 and 1879, offers some interesting insights into Victorian Walsham.

The Bank opened on the 7th May 1859 in the gabled red brick Institute and Reading Rooms, constructed in 1858 by the Martineau family and which, 150 years later, overlooks the Bowling Green. The following were the Managers and Officers of the bank:-

President – Richard Martineau Esq.

Managers – Revd. Rowland Ingram, Curate of Walsham; Revd. George Coulcher; Revd. Alfred Harlock of Westhorpe Rectory; H. J. Wilkinson Esq. Magistrate of Walsham Hall; F. M. Wilson Esq. of Langham Hall; G. E. Payne Esq.; T. M. Golding, Solicitor, of The Grove; J. W. King, Attorney, Four Ashes; W. Kent, Surgeon; J. Miller, Maltster and Farmer of the Maltings; H. M. Day; W. Taylor, Farmer, Wrenshall; H. Youngman; Watisfield Hall; J. Woodard, Farmer, Stanton Park; W. G. Hatton, Farmer, Sunnyside.

Trustees – T. M. Golding, J. W. King, J. Miller

Treasurer – J. Miller

Accountant/Secretary – Ziba Sones, Solicitor’s Clerk

This information was printed on the inside cover of each depositer’s record book. The bank opened every Saturday. There were seventeen Rules of Management governing the operation of the bank. These were between 7pm and 8pm, managers taking it in turn for one month to supervise operations and initial all the entries.

Rule 3 stated that, “deposits of not less than one penny will be received and interest of 3% will be allowed when the deposit amounts to 16s. 8d. No person to deposit more than £20 in one year, nor more than £100 in the whole.”

Rule 4 states, “One week’s notice must be given for the withdrawal of any sum exceeding twenty shillings.”

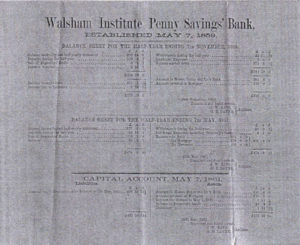

The Secretary, Mr. Ziba Sones, wrote to all the Managers on November 12th 1859, advising them that the first half year meeting of the bank would be “Monday 21st Instant at 11 o’clock in the Bankroom when and where the favour of your attendance is respectfully requested.” The half yearly report which accompanied the letter revealed the sale of 123 deposit books at one penny each and total deposits of £193 2s. 8d. by a total of 116 depositors. John Woodard of Stanton Park wrote expressing regret at not being able to attend the meeting and saying, “I feel I am a most unworthy member not having attended any meeting.” He further added “I wish I could prevail on some of my workpeople to make deposits but at present have not been able to do so.” Richard Martineau, writing from The Brewery, Chiswell Street, London, explained that “it will be out of my power to visit Walsham at present.” He enclosed a cheque for £5 as his subscription towards the preliminary expenses of the bank.

A circular written by the Secretary to those members who did not attend the meeting: Messrs Martineau, Wilson, Payne, Wilkinson, Woodard, Hatten and Youngman – Rule Xl stating that ” five managers shall constitute a meeting” had an added note “be pleased to say if there are any parties in Your District who may be disposed to join in the objects of the bank.”

A further meeting is arranged for 2ndJanuary 1860 to consider a proposal for advancing £110 on a mortgage of a real property. Very early on that day, the Revd. Alfred Harlock of Westhorpe Rectory wrote to say “I much regret that at the hour fixed upon for the meeting of Walsham Institute Savings Bank , I shall be engaged in superintending the distribution of some Parish Coal and shall in consequence be unable to be at the meeting this morning”

On the 5th January, 1860, Mr. Sones wrote a rough draft of a letter:

‘Dear Sir My sister Mrs Larter has never seen the colour of Robert Webb’s (Stowupland) money since she got judgement against him in your County Court. — Will you please have the kindness to enquire for me as to whether he has been working as normal and could you get some person to speak to the fact in order to satisfy the Judge that he ought to be cleared completely and will you kindly make the application to the Judge.’

One month later the Secretary wrote to Mr Hatten, “I beg to inform you that you are named as Manager to attend the weekly meetings in March.”

A note dated 28th April, 1860, and a further undated note, indicates the Revd, Alfred Harlock’s personal use of the bank and his success in persuading others to use the facility.

‘Mr Harlock will feel obliged to Mr Sones to place the enclosed to the accounts as below and keep the books forwarded until he calls for them.

- Alfred Harlock £1 5s. 8d.

- Mary Pryke 2s. 6d. (Deposit book 85)

- Joseph Pryke 2s. 4d. (Deposit book 87)

- Clara Pryke 1s. 10½ (Deposit book 88)

- Laura Pryke 3s. 1d. (Deposit book 89)

- Harriet Pryke 2s. 6d. (Deposit book 86)

Mr Harlock begs to forward at the same time his subscription, 10s. 6d.’

The Secretary’s second half year report, dated 7th May 1869, appears to paint a positive picture of the bank and, although eleven accounts were closed, seventeen new ones were opened and, as the notes above demonstrate, Mr Sones was kept busy holding the enterprise together and liaising closely with the Managers.

The report of May 1860 exists in both Mr Sones’ hand-written draft and the official version printed on blue quarto paper. It identified a total of 715 deposits, of which 356 did not exceed one shilling, and 25 were upwards of one pound, totalling £208 3s. 11d. There were 29 withdrawals totalling £172 12s. 2d. which included four heavy accounts being closed. The accounts closed totalled 20, but new accounts totalled 26. The profit and loss account showed a deficit of £1 14s.0½d. due to the Secretary’s salary and two years payment to Walsham Institute of £6 7s. for coals, candles and cleaning. Significantly, the Secretary was moved to pass judgement on those not using the bank, possibly the agricultural labourers who, in 1850 in Suffolk, earned a wage of 7s. 11d. compared to an average of 9s. 4d. nationally. He wrote:

‘Although it is to be regretted that the labouring and industrial classes do not more extensively avail themselves of the facilities offered by the bank for aquiring habits of thrift ans carefulness, it is sarisfactory to know that there are some of the rising generation amongst the depositors who, but for the means offered, would never at the present moment have had a shilling of their own.’

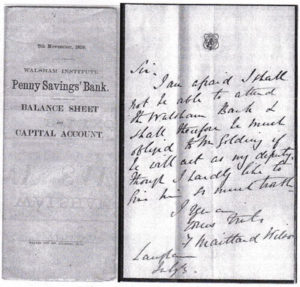

Records of the time show that the destitute were being lured north to the new industrial cities to live and work in abominable conditions. (See Review No. 56). Meanwhile the bank focussed on administration. F. Maitland Wilson, writing from Langham Hall, was concerned that rules should be adhered to:

‘Dear Sir, If you have not sent your notices to print I shall be obliged to you (to) alter the resolution I intend to propose at the next meeting as follows – that rule 10 having been superseded at a General Meeting without special notice, such suspension was not in accordance with the rules of the Bank. This will embrace both those which I gave you.

I remain

Yours Truly

F. Maitland Wilson.’

Such concern for the minutiae of bank administration in Walsham was soon overtaken by developments nationwide. The introduction of Rowland Hill’s prepaid postage stamp in 1840, of registered post in 1841, and of post boxes in 1855, were capped in 1861 by the establishment of the Post Office Savings Bank. The Revd. Richard Cobbold, Rector of Wortham, writing in 1860, noted that all the villagers went to the Village Shop to post their letters “for the Post Office is here established”. Here also the Paupers of the Parish met the Relieving Officer “to receive their flour and their pence”.

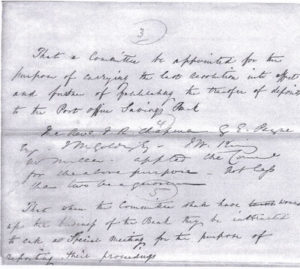

It was no surprise then that the Managers and Trustees of the Walsham Institute Penny Savings Bank considered winding up its affairs in ther face of the “facilities and security afforded by the Post Office Savings Bank”. Accordingly a special meeting of managers was called for 10 o’clock on Monday, 27th January 1862, in the Bank Room of The Institute. It was proposed…

‘that the establishment of a Post Office Savings Bank in this Parish entirely supersedes the necessity for the Walsham Institute Penny Savings Bank and that the business of this Bank be therefore terminated and its affairs wound up in accordance with Rule 17.’

(Rule 17 stipulated two-thirds of the Managers present shall so resolve.) The Secretary, Mr Ziba Sones, recorded the vote as 7 for and 3 against and went onto detail what else needed to be done for “the carrying of the resolution into effect”.

There is an absence of documents for nearly ten years after the meeting of 27th January 1862 but a Penny Savings Bank continued until at least 1879 although not, it seems, sponsored by the Post Office.

The three original Trustees were still in place together with Ziba Sones as the Accountant. There were seven new managers replacing, one assumes, the seven who voted for closure. Four of these newcomers were young entrepreneurs replacing members of the landed gentry and the three Church of England clergymen. They were…

- Henry Miller Brewer Maltster aged 19

- William Colson Farmer of 24 acres aged 42

- Henry Drake Master Plumber Decorator aged 26

- P. Youngman Butcher aged 31

The Depositors’ Record Books were the same, save that a new cover had been pasted over the old one to read: Walsham le Willows Penny Savings Bank.

In 1879 the bank still operated on Saturdays between 7pm and 8pm and only one of the seventeen rules of management was changed. In Rule 10, reference to “all investments being in the Bury Savings Bank” was removed. As to the success of the new bank operation, one can but compare the half year reports of November 1859 and September 1872, which demonstrate that over the 13 year period, the assets of the bank rose from £188 12s. 8d. to £914 14s. 1½d., proving the bank to be a useful community facility. A number of the depositors were women like Minnie Stevens, Edna Easlea, Bertha Easlea, Angela Golding, Laura, Clara, Mary and Harriet Pryke and Edith Nunn. While individual deposits for the half year averaged a little less than one pound, one person made 25 deposits over a 3 year period to accumulate a total of 6s. 6d., about 33p in today’s money, but representing considerably more in spending power.

In conclusion, I have a picture of small handwritten notes being carried between villages, sometimes at very short notice by people galloping on horseback; of managers being unable to attend meetings at 10 o’clock on Monday mornings because of the pressure of other commitments both locally and in London; of unrealistic expectations that the labouring and industrial classes had a surplus of monies to deposit; of a rising class of entrepreneurs ready and able to assume responsibilities on behalf of their community. Perhaps I am making too much from this small handful of original documents, but they, and others like them – contemporary newspaper reports, mortgage arrangements, diaries, minute books, details of house sales, surveys and assessment for tithe payments, are all we have to offer an insight into the nature of the village years ago.

Do you have any documents which you would like the History Group to examine and interpret?

Rob Barber

Acknowledgements

- Walsham Institute Penny Savings Bank – original documents

- Walsham le Willows Penny Savings Bank- original documents

- Bury St Edmunds Record Office

- Steve Colby

- Prothero’s English Farming Past and Present

- Richard Cobbold’s Biography of a Victorian Village, edited by Ronald Fletcher.

Editors note

Ziba Sones’ infant son, also called Ziba, is buried in the churchyard. The unusual name is biblical (2 Samuel 9) and he was character noted for his loyalty.

The Bury Post

In 1782 a local newspaper, the Bury Post and Universal Advertiser, was first printed. It was a four page weekly journal costing 3d. Later it was to become the Bury and Norwich Post.

The earliest mention of Walsham-le-Willows appeared in an October 1783 issue of the paper.

October 1783

‘Notice is given that eleven fine poll’d cows (Pollarded i.e. horns removed) of the Suffolk breed the property of Mr. John Sparke is to be sold at auction at Mr. Bryants Chequers Inn.’ (The thatched property on the right when coming into Walsham from Badwell Ash).

March 1784

‘A house very pleasantly situated near the church comprising of an excellent hall, a large handsome parlour and a small common parlour, four good sleeping rooms with closets, and three exceedingly good garrets, a good kitchen, pantry, store room, and fuelry. There is also a kitchen garden planted with fruit trees, in which there is a lead pump supplying excellent water. There are offices for wood, coals, and brewing utensils, and a two stalled stable that could be enlarged at a trifling expense. To be sold at the same time is a very neat cottage adjoining the above premises that has a piece of garden and a well supplied with good water. Walsham is a large pleasant village in Suffolk the residence of several genteel families.’ (This almost certainly Prior’s Close.)

June 1785

‘A good post windmill with boulting mill, two pairs of stones, troughs, ropes, going gears, and appurtenances all in excellent condition. To be sold as stands and removed at the buyer’s expense or the purchaser can be accomodated in two thirds of the land on which the said mill is erected.’ (This mill was situated in Crownland Road.)

December 1787

‘Some thieves have broken into the warehouse of Mr. Walne the Walsham shopkeeper and stole three firkins of butter and a quantity of candles with which they got clean away. A reward of three guineas is offered on the conviction of the offenders. If an accomplice will impeach another accomplice he shall be entitled to the same reward.

In the last Review No.58, about the violence at the Walsham Gala, the following appeared a week after in the local press:

Storms of exceptional severity hit the village of Walsham with deafening peals of thunder and the most vivid lightning. A farm labourer named Payne was thrown to the ground and rendered unconscious, although thankfully for a short time. Amongst other damage the chimney of the girls school was struck. The electrical fluid passed down the chimney dislodging brickwork and scattering soot and debris over the floor which terrified the teacher Mrs Beart and about 30 children.

After the violence the week before the villagers must have thought that a Godly judgement had descended upon them.