The story of Herbert Pike, a 19th century Apprentice

There are people in Walsham today who well remember the Clamp family. They seem to be descended from Samuel Clamp who, after his first wife Mary’s death in February 1766, married Lucy Archer on 1st July 1766 by whom he had nine children to add to the three by his first wife.

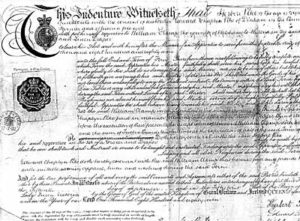

There are some gaps in the record before, at the turn of the 19th/20th century, we find George recorded as a blacksmith at Bridge House; Clarence was carrying on a saddler and harness makers business at Avenue House where his wife also had a sweet shop; William was apprenticed to Mr Carter a master draper and grocer in High Street and obviously did very well for himself for sixteen years later, William himself was the master draper and grocer at the same address (the Old Stores and Yew Tree Cottage). It was here that he signed an indenture accepting Herbert Pike on a four-year apprenticeship.

Herbert Pike was born at Standwell Farm, Denham near Eye and his grandparents both came from Palgrave, the Pikes being farmers and maltsters while the Chaplyns were corn millers It was this background which provided the not inconsiderable sum of twenty-five pounds needed to secure the apprenticeship of Herbert with William Clamp in 1887. One wonders why Herbert was not prepared to carry on the family farming enterprise. Was it the bite of the depression in agriculture, which saw many leave the land or perhaps he just disliked farming life?

Whatever his feelings, Herbert’s father paid the first instalment of £12 and ten shillings. In return William Clamp promised to teach and instruct Herbert “the Art of a Grocer and Draper, finding unto the said Apprentice sufficient meat, drink, lodging and all other necessaries during the said term.” Herbert’s father, for his part, promised William Clamp that “he will find and provide the said Apprentice with suitable wearing apparel, linen and washing during the said term.”

For his part, Herbert Pike “the Apprentice his master faithfully shall serve, his secrets keep, his lawful commands everywhere gladly do. He shall do no damage to his said master nor seek to be done of others but to his Power shall tell or forthwith give warning to this said Master of the same. He shall not waste the Goods of his said Master nor lend them unlawfully to any. He shall not contract matrimony within the said term nor play at Cards, Dice or Tables or any other unlawful games. He shall not haunt Taverns or Playhouses nor absent himself from his said Master’s Service day or night unlawfully but shall behave in all things as a faithful Apprentice.”

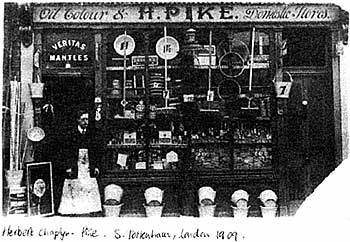

Having lived under such strictures for four years one can appreciate the wish of the apprentice to escape and be his own master. So it was that Herbert Pike was photographed in 1909 outside his own Oil Colour and Domestic Stores in Philip Lane, South Tottenham, London. Ambition achieved at the age of 39? It would seem not, for in 1912 he left it all, emigrated with his family to Canada where he worked as a mechanic on the Canadian National Railway in Winnipeg. This abrupt career change was confirmed two years later when, at the outbreak of World War One in 1914 Herbert joined the Royal Flying Corps in Toronto.

Although his daughter Ella, and later his granddaughter, ran a thriving town grocery store in McCreary, Manitoba until recently, I am left wondering how Herbert coped with an upbringing on a farm, then working as a shopkeeper before seeming to find his true vocation, at the age of 40 and in a foreign land.

Rob Barber

With thanks to Brenda Richardson of Colchester.

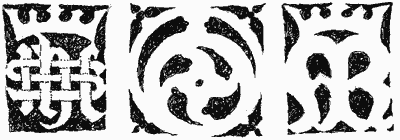

Walsham’s Mystery Symbol

On the exterior clerestory of St Mary’s Walsham le Willows is a series of flint flushwork panels (white limestone inset with black knapped flints). In common with most work of this kind, it is late 15th century. At the east end of the north side, a focal point from Walsham Street, are three large panels, significant rather than merely decorative. No.1, looking deceptively like a portcullis, is Christ’s crowned symbol: the first letters for ‘Jesus’ in Greek (“ihc”) intertwined with a large “S” for “sanctus” (holy). No.3 shows a crowned “M” containing a lesser circle off-centre. With minor variations it appears twice more in smaller panels on the clerestory, one on the north-west and the other on the south-west. It is also found at high points on all four buttresses of the tow at neighbouring St Mary’s, Badwell Ash. Both churches were in the care of nearby Ixworth Priory which would have governed the buildings’ decorative schemes. Only yards from the Priory site, Ixworth church, also dedicated to St Mary, has the circle device at the base of the tower’s south-west buttress.

There is written evidence for Badwell Ash tower being the work of Thomas Aldrych, an important mason of North Lopham, just over the border in Norfolk. He worked at Badwell Ash during the 1460’s and Ixworth tower bears the date 1472. Documents suggest that Walsham’s clerestory was built at about this time, but Aldrych is not mentioned. Although he may well have been involved in all these building programmes, the circle device must on no account be regarded as Aldrych’s personal emblem or “mason’s mark”. If it were, the placing of the panel at Walsham between the sacred symbols of Christ and the virgin would make Aldrych guilty of the most deadly sin “superbia” (pride).

Possibly the device relates to Isaiah ch.40 v.22 where God is described in the King James version as “He that sitteth upon the circle of the earth” or, as medieval churchmen would have known the text: “Qui sedet super gyrum terrae”. The only other time this word for circle appears in the Latin Bible is in a similar passage about God and the round world: “et gyro vallabat abyssos”, Proverbs ch.8 v.27, (“when he set a compass upon the face of the depth”). God was usually pictured creating the earth as a globe, and Columbus was confident in 1492 that he could said round the world to China.

The circle device is similar to the brass apparatus called an astrolabe developed by the Arabs. It was used to study the stars and find the position of Mecca. Handheld, and only about six inches in diameter, the earlier types had a small disc mounted off-centre upon a larger disc. An English prose “Treatise on the Astrolabe” was written in 1391 by Geoffrey Chaucer for his ten-year-old son Lowys. The boy would have needed more than Level 5 Maths to understand the calculations involved. (Incidentally, Lowys’ nieces Alice de la Pole, the poet’s granddaughter, held Walsham manor 1450 – 1475.)

Chaucer’s text has a great deal about the study of the “zodiak”, which in his time was “astrologoie”. To us this seems mere superstition, but to the late medieval mind it was part of the divine scheme. The famous “Tres Riches Heures” by the Limbourgs, c.1416, has saints’ days and zodiacal data all interspersed, and this was common in literature. Chaucer mentions “rewles in astrologie” as being presided over by “God and his Moder the Maide”, and interestingly the main circle device at Walsham is also set between symbols of God the Son and His mother.

With the Isaiah text about the circle of the earth it seems that the device is intended as a symbol for the heavens. This view is reinforced by the small shapes at the four corners of the panels. While the design on the inner circle varies with all the examples quoted, the devices at the corners are consistent, integral rather than merely ornamental. They are like paired wings and call to mind John Donne’s Holy Sonnet “At the round earths imagin’d corners, blow/ Your trumpets, Angells,”. Admittedly Donne’s paradoxical poem dates from 1610, but he is echoing older writings. Revelation ch.7 v.1, reads in the Latin translation as: “quatuor angelos stantes super quatuor angulos terrae”. Avoiding the pun, the King James version has: “four angels standing on the four corners of the earth”. In Jewish tradition these angels represent the four winds.

Combining the texts, the image is of the four winds at the “angulos terrae” (Revelation ch.7 v.1) surrounding God who sits upon the circle of the earth, the “gyrum terrae” (Isaiah ch.40 v.22). The repeated shapes look like angel forms gyrating through the universe, reminiscent of Dante’s vision long before in 1300.

(I am grateful to Philip Aitkens, John Blatchly and Clive Paine who have discussed this mysterious device with me).

Brian Turner 2003

Books consulted

- Alexander, J . & Binski, P. (eds), Age of Chivalry, London 1987

- Biblia Sacra, Vulgatae Editionis, Paris 1868

- Garrod, H. W. John Donne Poetry and Prose, Oxford 1946

- Hart, S. Flint Architecture of East Anglia, London 2000

- The Holy Bible, Authorised Version: Cambridge

- Longnon, J. (ed), Les Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, London 1989

- Novum Testamentum Graece, 1881 edn: Oxford

- Robinson, R. N. (ed) The Complete Works of Geoffrey Chaucer London 1978

Latest

Sheryl Pamment from Victoria, Australia has just been in touch having seen the Quarterly Review about transportations on the web site. Zachariah Pamment, transported from Walsham for seven years for stealing glass, had a son Zachariah (in Australia) who had a son James Ernest born 1875 who married Eliza Jane Beard in 1903. After 1922 James and Eliza adopted Sheryl’s grandfather after his mother had died and he took on the name Pamment. (See Review No. 7 for further details)